|

Buon Natale e

Buon Anno a tutti!

From your friends at La rondine

|

DECEMBER MEETING

A Special Celebration of Christmas

with The Panettone Players

|

Every December we celebrate the holiday season in two

ways. Traditionally our Christmas program always includes an original

performance by the Club’s own little theater group, The Panettone Players.

We are very proud of this group. Although their performances are

very short, averaging about 20 minutes, each one represents a truly creative

work, written specifically for the occasion of the Club’s December meeting.

This year they will bring to us an original English language adaptation

of a play by the very famous Eduardo De Filippo, Natale in Casa Cuppiello.

The Player’s version, titled Vignettes from Natale in Casa Cuppiello,

captures the essence of De Filippo’s story of Luca Cuppiello, who each

year builds a presepio or nativity scene as a symbol of the harmony that

he wishes for his own very dysfunctional family. It is a story of

hope born anew from the depth of denial.

Additionally, we celebrate the holidays through those special

cultural metaphors for which Italy is famous worldwide – fine food and

good wine – symbols of the Italians’ love for life in all its richness

and pleasure, by arranging a really wonderful and very special dinner.

A copy of the menu for this dinner is enclosed.

The cost of the dinner is $40 per person. Because

of the advance preparations required, we must have your reservations

by December 14. We are strictly limiting attendance to 72 people

and will be unable to accommodate late reservations or “walk-ins.”

Send Reservation Form with Payment to Marie Wehrle, 8389 Weber Terrace

Drive, St. Louis, MO 63123. (314) 544-8899.

|

|

Next Meeting Wednesday, December 19, 2001

Cocktails 6:30 PM - Dinner 7:00 PM

Da Baldo's Restaurant

See above for reservations

|

RECAP OF NOVEMBER

MEETING

Brunelleschi’s Dome

An Engineering Perspective

|

| Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) was one of the greatest

architects of the Italian Renaissance and the dome of the Cathedral of

Florence (Santa Maria del Fiore) is probably his most recognized work.

In our November presentation, speaker Gene Mariani, presented Brunelleschi

primarily as an engineer rather than architect, discussing why the dome

is one of the greatest engineering feats of the Renaissance. Trained

as a goldsmith, in 1401 Brunelleschi entered the famous design competition

for the bronze doors of the Cathedral’s Baptistery. Having lost to

Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455), he completely abandoned sculpture and embraced

architecture, moving to Rome, where for 13 years he studied its ancient

classical forms. After returning to Florence in 1418, he entered

the competition for the design of the dome of the cathedral. His

old rival Ghiberti was his main competitor, but Brunelleschi’s approach

prevailed and he was declared the winner.

The construction of the great dome, the largest in the

world, presented seemingly insoluble engineering problems. Work would

begin at the 170 feet level (at the top of the drum above the cathedral

nave), and, most challenging, the dome was to be built without any exterior

buttressing (traditionally used to reinforce cathedral vaulting) and without

centering (the interior wooden framework that had been used to support

arches and domes and keep bricks and stones until the mortar set).

Although Brunelleschi was one of the greatest of Renaissance architects

as clearly shown by his Ospedale degli Innocenti, the sacristy of

San Lorenzo Church, and other works, the dome’s architecture was relatively

straightforward and conventional, its eight-sided form being modeled after

the Baptistery and its pointed-arch shape based on the gothic style.

But it was in the engineering that Brunelleschi’s genius

came forth. After briefly comparing the work of an architect to that

of an engineer, Mariani presented the dome from an engineering perspective,

discussing the basic principles of structural engineering, unknown in Brunelleschi’s

day – the use of statics to determine how loads on structures resolve themselves

in the form of forces, the use of stress analysis determines the type,

magnitude, and direction of stresses caused by these forces, and the use

of structural analysis to determine the requirements of structural members

to resist these stresses successfully. The construction of domes

presented special problems, the first being how to resist the lateral thrust

at the base of the huge structure without exterior buttresses and how to

resist the interior hoop stresses in the shells without making them extremely

thick; the second problem was how to keep the bricks in place against gravity

until the mortar set.

Using schematic and sectional diagrams, Mariani presented

Brunelleschi’s solutions. To solve the first problem, Brunelleschi

used four massive stone chains linked with iron clamps to encircle the

dome shells at equally spaced points. In addition, a wood chain was

used between the first and second stone chains. Iron chains may have

been also used to supplement the stone chains, although there is no evidence

that this was ever actually done. Like hoops around a barrel, these

chains successfully contained the Dome’s lateral thrust forces and internal

hoop stresses. Brunelleschi’s solution to the second problem, locking

the brickwork in place while mortar set, involved two approaches:

the first was to use uniquely shaped bricks set in a herringbone pattern;

the second, was to use nine rings or circles of brick which encircled the

dome at points between the first and fourth stone chains. These rings

were originally thought to have been used to help the chains resist lateral

forces; it was not until the 1970s that it was determined they were not

intended for that, but to serve as horizontal arches locking the brickwork

in place in the manner an arch locks its members in place under load.

It was found that without these nine rings (it was rumored that Brunelleschi

chose nine based on Dante’s nine circles), the herringbone brick pattern

alone would have been insufficient to keep the brickwork in place.

The work on the dome began in 1420 and was completed in

1436. The Lantern, which Brunelleschi designed but he did not live

to see completed, was then begun.

Eugene Mariani, President of the Italian Club, is an Adjunct Professor

in the School of Engineering and Applied Science of Washington University.

He is a graduate of St. Louis and Washington Universities and has a Ph.D.

in Engineering Management from the University of Missouri – Rolla.

|

|

L’ANGOLO DEL PRESIDENTE

By Gene Mariani |

WELCOME NEW MEMBERS

We are pleased to announce that three new members were elected at the

November 2001 meeting. We wish to extend a warm welcome to Regina

Beno, Filippo Ferrigni, MD and Elisa Valenti-Hart.

|

CONDOLENCES

On behalf of the Club, the Board of Directors wishes to extend its

sympathy to Member Dr. Robert Pisoni on the death of his mother,

Mrs. Josephine Pisoni.

|

|

THANKS AND MORE THANKS

Many thanks to everyone who helped on the October 19 showing

of the classic De Sica film, Il Generale Della Rovere, which

was co-sponsored by the Club and The Saint Louis Art Museum: Carla

Bossola for her wonderful introduction, Marie and Richard

Brand,

Marie and George Wehrle, Gloria and Charles Etling,

James Tognoni, Susan Mariani, Christopher Taege, Marsha

Lang, Pauline Klein and especially Barbara Klein for

all of her work on the PR and the various displays ….plus coming all the

way from Milano to help out.

Many thanks also to Carla Bossola, Dorotea Rossomanno-Phillips,

Vito

Tamboli, and Aldo Della Croce for all of their work on the Club’s

Classic Italian Film and Opera Series at the Bocce Club. Two Nino

Manfredi films were shown, Pane e Cioccolato and In Nome del

Papa-Re, and two Puccini operas, Madama Butterfly and

Tosca.

Thanks also to the Bocce Club for the use of their facilities.

And thanks to all who helped with our Giacomo Leopardi

Seminar. In particular, Carla Bossola for conducting the weekly

sessions, Dorotea Rossomanno-Phillips for her administrative help, and

Edward Berra for providing the wonderful meeting room at the Southwest

Bank.

|

|

|

| |

|

Notes

from Italy(Submitted by Barbara Klein)

LA SCALA WILL CLOSE

FOR A THREE YEAR RENOVATION

|

| December 7th, the feast of Milan’s patron saint, St. Ambrose,

is the traditional opening day of the city’s opera season; this December

7th however, is special as it is not only the first night of the new season

at La Scala opera house, but it is also the last opening night at this

famous venue until December 7, 2004. During the intervening period,

La Scala will undergo a much needed renovation, including a complete overhaul

of the technical layout of the stage.

La Scala was founded under the auspices of the Empress

Maria Teresa of Austria to replace the Royal Ducal Theatre, which was destroyed

by fire on February 26, 1776 and had been home of opera in the then Austrian-controlled

Milan. As the new theatre was built on the site of the former church

Santa Maria alla Scala, it has since been referred to as “Teatro alla Scala”,

or simply “La Scala”.

The great neoclassical architect Giuseppe Piermarini designed

La Scala, which opened on August 3, 1778. In fact, locals often affectionately

refer to the theatre as “il Piermarini” in honor of the man who built this

beautiful and acoustically amazing building. (It is interesting to

note that it took less time to build the theatre in the 1770’s than it

will take to renovate the theatre today!) In 1943, La Scala was severely

damaged by bombing, and the upcoming closing will mark the first time since

World War II that the theatre will leave its historic site in Piazza della

Scala.

The December 7th performance will be one of eight performances

in December of Otello, by Giuseppe Verdi, which will be directed

by Riccardo Muti and feature the great Placido Domingo, alongside Barbara

Frittoli and Leo Nucci. The last performance on December 30, 2001,

will not only be the last performance at La Scala for the next three years,

but it will also mark the end of the centenary year of the death of Giuseppe

Verdi, during which La Scala performed eleven Verdi operas in his honor.

Beginning on January 19, 2002, and for the next three opera

seasons, all performances will be held at the Teatro degli Arcimboldi,

which is located in the Bicocca section in northern Milan. The Arcimboldi

is a modern and spacious theatre that was just completed in 2001.

It has 2,500 seats, 700 more than La Scala, but will not have any of the

traditional standing room only seats. Verdi’s masterpiece La traviata

will inaugurate this new theatre.

This year’s opera season will include, besides Otello

and La traviata, Samson et Dalila, Salome, Boris

Godunov, Le nozze di Figaro, Madama Butterfly, Il

barbiere di Siviglia, Lucrezia Borgia, and Rigoletto.

Placido Domingo will appear in Otello and Samson et Dalila. For further

information, including a complete calendar and ticket availability, check

out the website at www.teatroallascala.org.

|

|

OLDEST NATIVITY SCENE

|

The oldest intact presepio, or nativity scene,

is a painted wood carving of the Holy Family and the three wise men done

in 1370 by Simone dei Crocefissi. The six statues, referred to as

the “Adorazione dei Magi”, are on display in the Chiesa del Martyrium,

which is one of the seven churches comprising the Santo Stefano complex

in Bologna. The statues, which are approximately half of life size,

were recently restored to their original splendor revealing the artist’s

rich gold, red, and blue colors. |

|

The Italian Club of St. Louis

|

|

|

|

| I capolavori della poesia italiana

40. Giovanni Pascoli (San Mauro di Romagna 1855 – Bologna

1912) a dodici anni fu colpito da una tragedia che lascierà un’indelebile

impronta sulla sua vita: l’omicidio del padre, medico condotto, mentre

tornava a casa sul calesse, evento immortalato dalla sua famosa poesia

“La cavallina storna.”

Il Pascoli condusse una vita tranquilla insieme alla sorella Mariù

e fu insegnante prima di liceo e poi di università. Nel 1905

successe al Carducci nella cattedra di letteratura italiana all’università

di Bologna. Tra le sue raccolte di poesie sono da segnalare Myricae

(1891), Poemetti (1897), Canti di Castelvecchio (1903), Poemi conviviali

(1904), Odi e Inni (1906). L’assiuolo fu pubblicato nel 1897 nella

quarta edizione di Myricae.

L’assiuolo

di Giovanni Pascoli

Dov’era la luna? Ché il cielo

notava1 in un’alba di perla

ed ergersi il mandorlo e il melo

parevano a meglio vederla.

Venivano soffi di lampi

da un nero di nubi laggiù;

veniva una voce dai campi:

chiù…2

Le stelle lucevano rare

tra mezzo alla nebbia di latte:

sentivo il cullare del mare,

sentivo un fru fru tra le fratte;

sentivo nel cuore un sussulto,

Com’eco d’un grido che fu.

sonava lontano il singulto:

Chiù…

Su tutte le lucide vette

tremava il sospiro del vento;

squassavano le cavallette

finissimi sistri3 d’argento

(tintinni a invisibili porte

che forse non s’aprono più?…)

e c’era quel pianto di morte…

chiù…

1 giacché il cielo nuotava.

2 (Il verso dell’assiuolo, un piccolo uccello

rapace notturno che secondo la tradizione contadina è presago di

morte).

3 (Strumenti musicali di antica origine

egiziana che venivano usati nel culto di Iside nella cerimonia di resurrezione

del marito Osiride). |

|

LA STORIA D’ITALIA

| (Continua dal numero precedente)

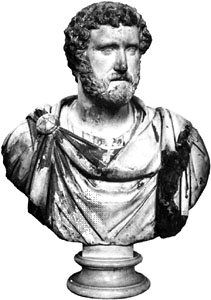

29.

Antonino il Pio (86 - 161) (Imperatore 138 - 161).

Alla morte

di Adriano, Antonino aveva già 53 anni e nessuno si sarebbe aspettato

che avrebbe regnato così a lungo. La sua famiglia veniva da

Nîmes, in Provenza, ma già da molti anni si era trasferita

a Roma dove aveva accumulato un immenso patrimonio, con poderi in Campania,

Etruria, Umbria, nel Piceno e nel Lazio. 29.

Antonino il Pio (86 - 161) (Imperatore 138 - 161).

Alla morte

di Adriano, Antonino aveva già 53 anni e nessuno si sarebbe aspettato

che avrebbe regnato così a lungo. La sua famiglia veniva da

Nîmes, in Provenza, ma già da molti anni si era trasferita

a Roma dove aveva accumulato un immenso patrimonio, con poderi in Campania,

Etruria, Umbria, nel Piceno e nel Lazio.

Nel 117 Antonino aveva sposato Faustina Maggiore, sorella di

Annio Vero, il padre di Marc’Aurelio, ma Faustina morì nel 140 lasciandolo

con una figlia, Faustina Minore (che più tardi sposerà

Marc’Aurelio) e i due figli adottivi Marc’Aurelio e Lucio Vero, che, come

vedremo più avanti, saranno ambedue imperatori.

Al contrario di Adriano, che aveva passato quasi tutta la sua vita viaggiando,

Antonino non si mosse mai dalle sue residenze in Campania. Non gli

piaceva viaggiare, aborriva lo sfarzo, era semplice di gusti e preferiva

vivere nella sua campagna dove i riti e le credenze erano arcaici, legati

alla terra, alla fertilità e ai cicli vegetali, come lo sono in

tutte le antichissime tradizioni nel mondo. Preferiva la pace e affidò

ad altri la direzione delle guerre e l'amministrazione dell'impero.

Antonino decise di non ingrandire l’impero, cercando soltanto di mantenere

i confini e placare le rivolte che scoppiavano di tanto in tanto.

Nel 142 le legioni romane combatterono contro i Briganti in Britannia e

costruirono una seconda linea di difesa a nord del Vallo di Adriano, il

Vallo di Antonino. Altre rivolte ebbero luogo in Egitto, Armenia,

Mauritania e Germania.

Fu molto parsimonioso e pur dimostrandosi moderato nel far pagare le

tasse, non fu meno prodigo dei suoi predecessori nello spendere grosse

somme per le elargizioni al popolo (ne fece 9, in denaro e grano), ai soldati,

ai bisognosi, alle ragazze madri e ai bambini illegittimi. Per onorare

la memoria della moglie Faustina, Antonino fondò Puellae Faustinianae,

un’istituzione caritatevole per le ragazze povere.

Antonino costruì il tempio di Adriano nel Campo Marzio, un tempio

in onore di Faustina nel Foro e completò il mausoleo di Adriano

sul Tevere. Alla sua morte lasciò all’impero un surplus

675 milioni di denarii.

(continua al prossimo numero)

|

|

|