PART

ONE

From

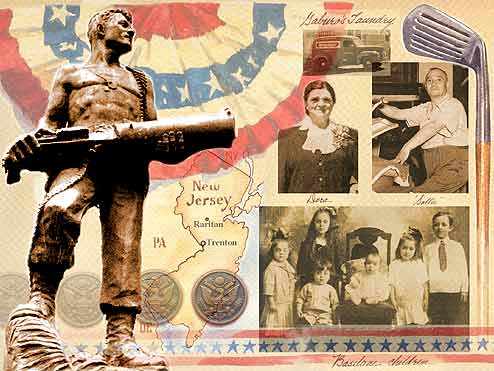

Goospatch to American icon

A

high-strung kid from Raritan, N.J., Johnny Basilone searched for direction.

He found the Army, the Marines and then huge trouble.

The

Orange County Register

By

Keith Sharon

Illustrations

by Craig Pursley

Sunday,

September 19, 2004

If the snow was packed hard, the kids from Goosepatch could belly-flop on a sled all the way across the highway, across the railroad tracks and into downtown Raritan, N.J.

They had to dodge horse-drawn carriages, rickety cars and the occasional train, but if they leaned just right, they could make it. And that's about as far as the kids from Goosepatch could go.

The slightly higher elevation was about all the derisively named neighborhood had to offer – other than the wild geese, which outnumbered the people. It was the outskirts of town, the side of the tracks most kids didn't want to be from.

The Basilones - by 1932 there were 12 of them - lived in half of a wood-frame duplex on First Avenue. Downtown Goosepatch. Six boys, four girls, two bedrooms, one bathroom. They shared the house with the Bengivengas, a tiny family of four.

Goosepatch was made up of immigrant Italians and Poles, who, like their neighborhood, were known by less-than-flattering nicknames.

"We weren't considered Americans," said Carl Bengivenga, who still lives in Raritan. "We were Italians. Second-class citizens."

The reporters, who later flocked, like geese, to Raritan, never mentioned Goosepatch when they wrote the incredible story of Johnny Basilone.

By the end of World War II, Johnny was an all-American hero, the only enlisted man in that war to receive the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross - the two highest military honors that can be awarded. Gen. Douglas MacArthur called him a "one-man army."

He was part Joe DiMaggio, part John Wayne. His ears, people wrote, were like Clark Gable's. Imagine, movie-star ears.

His name and likeness, over the past 60 years, have been immortalized from coast to coast. Beginning in San Clemente, a 17-mile stretch of the San Diego (5) Freeway (along the entrance to his adopted home, Camp Pendleton) is named for Basilone, as is Basilone Road, which leads to the San Onofre nuclear power plant. A bridge, a football field, an American Legion post and Marine detachment are named for him in New Jersey. A nationwide petition drive is gathering signatures to get Basilone honored with a postage stamp. The USS Basilone was a proud battleship until it outlived its effectiveness and was sunk.

Still, it's fitting that the statue the Raritan borough commissioned in his honor, the one the bands still march toward in the annual John Basilone Memorial Parade, the one that depicts him bare-chested and cradling a machine gun, is on the outskirts of town.

Because when someone today hears what happened to Johnny Basilone - from his brazen exploits on the battlefield, to his instant stardom, to the shocking decision he made - they always ask the same question.

Why?

The people who knew him, the people who idolized him and the people who have studied his life all offer a version of the same answer.

His sense of duty, his ambition, his warrior spirit, his new identity - everything he had become - drove him away from Goosepatch. When Johnny came marching home again, he couldn't stay.

• • •

Johnny Basilone was a goof. It took him 10 years to complete eight grades at St. Bernard's Parochial School. In his eighth-grade yearbook, his hobby was listed as "chewing gum." His life's ambition was to be an "opera singer." He was "the most talkative boy" in his class. When the nuns threatened to take conduct points away from him, he uttered what the yearbook recorded as his favorite saying, "Take them all."

On hot days, Johnny and his buddies liked to cut school and head to the B.A.B., an acronym the boys gave the Raritan River. B.A.B. got its name because of the boys' choice of attire when they swam - Bare Ass Beach.

The Madhouse (a nickname the boys gave the Empire Theater) was another of Johnny's hangouts. You could get into a silent picture for a dime. And you could sneak your friends in through the side door for free. Johnny and his buddies would bring fruit and vegetables to heave at the screen if the exploits of cowboy stars Tom Mix, Hoot Gibson and Tim McCoy ever got boring.

His father, Salvatore, or Sallie, as his friends called him, scrimped and saved as a tailor's assistant until he had enough cash to open his own shop. There weren't too many kids in Goosepatch who wore gabardine pants. But Johnny did.

A sickly man, Sallie was a soft touch when it came to his kids. Once, when Johnny got caught stealing apples from a nearby farm, it was his mother, Dora, who lowered the boom.

"I smacked him good," she later told reporters.

Johnny was 15 when he finished eighth grade, and no amount of cajoling could make him go to high school. Most kids from Goosepatch, who had no expectations for college or much of anything for that matter, ended up working in the wool mill. Johnny's mother had been a mill worker.

But Johnny wanted something bigger.

Johnny got his first job as a caddie at the Raritan Valley Country Club. He made about 40 cents a day. Caddying, however, had one inherent flaw, as careers go: Winter.

In the fall of 1932, faced with snow and very little golf, Johnny got a second job. He worked as a driver's assistant for Gaburo's Laundry. A driver's assistant didn't drive. A driver's assistant unloaded and delivered the clothes.

Tiring work.

So tiring, in fact, that Johnny got caught sleeping on a pile of laundry. Old man Gaburo fired him.

Johnny's older sister, Phyllis, one of the many chroniclers of his life, wrote that her under-employed, restless brother finally found a direction for his life in June of 1934.

At the dinner table one night, he announced: "I'm joining the Army."

The Army, he was convinced, offered adventure. It meant seeing the world outside Goosepatch. In peacetime 1934, war wasn't part of the equation.

Johnny insisted on saying his goodbyes at the Basilone home. He didn't want a public scene. His family watched from the porch as Johnny headed to the train station.

Phyllis wrote that she could see Johnny crying as he walked away.

It wasn't long before Johnny found adventure. And respect. And camaraderie. And purpose.

And a girl named Lolita.

• • •

They didn't have girls like Lolita in Goosepatch.

By 1934 standards, Johnny was assigned to the best duty a G.I. could ask for. There was no hint of war. Manila was the "Pearl of the Orient." Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who lived in a seven-room suite in the Manila Hotel, had established a military base there, and Filipino-American relations were at an all-time high.

Johnny was assigned to machine gun detail. He got so proficient at taking apart and putting together weapons, that officers brought their malfunctioning guns to Johnny for fixing.

His avocation was Lolita.

She became his exotic guide to this new world. She took Johnny across the Pasig River onto Calle Escolta, the main thoroughfare of old Manila. She took Johnny along the waterfront where homes were built on stilts, and pigs and chickens lived under the floorboards.

The problem with falling in love in - and with - a foreign land is that, at some point, your ship has to leave.

Johnny told Lolita that he would take her back to the States and marry her. But in June of 1937 when he was set to ship out, he decided to leave Lolita behind.

To say that Lolita didn't understand would be an understatement. Rufus "Bunky" Stowers, one of Johnny's closest friends in later years, heard the story a million times.

Johnny was out when Lolita came into the barracks looking for him.

She had a machete with her.

"She cut his sea bag in half," Bunky said with a laugh.

It is unclear when, precisely, Johnny got his nickname. Newspapers reported that his Army boxing coach - Johnny fought as a light-heavyweight - began calling him "Manila John," as if he owned the city. Others, such as Bunky Stowers, said the nickname came later, and when Johnny wouldn't shut up about the Philippines.

"He loved to talk about Manila," Bunky said.

• • •

Johnny came home to Raritan like he left.

Quietly and alone.

He simply showed up in his mother's kitchen. Dora was making spaghetti when she turned around, and there he was.

He was 21, bigger, different. He had a girl tattooed on his right arm, and a knife piercing a heart with the words "Death Before Dishonor" on his left. She hugged him and cried.

But somehow, all his experiences in the big world outside Raritan added up to not-so-much in Goosepatch. Within a month or so, he was just another man looking for work. He returned to caddying at the country club.

When winter hit, he got a job as a laborer at the Calco Chemical plant.

Johnny couldn't take it.

In 1938, he moved in with sister Phyllis in Reisterstown, Md., and got a job at the Philgas Company. He planted metal tanks outside homes so housewives could cook on gas stoves.

Thrilling.

Johnny thought about the military again. But this time, the stakes were higher.

On Sept. 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, England, France, Australia and New Zealand declared war on Germany. American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt said this country would stay neutral, but neutrality became a harder and harder sell.

In July of 1940, Johnny Basilone told his father he had enlisted in the Marines.

Johnny couldn't bring himself to tell his mother. So his father did it for him.

• • •

In his first year, Johnny went from Quantico, Va., to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to Culebra, Puerto Rico, back to Quantico, to Parris Island, S.C., to New River, N.C. Usually, they were steaming, desolate places designed to prepare the Marines for jungle or beach warfare.

At the start of the 1940s, Johnny was part of a standing military of fewer than 200,000 troops. The United States had the 17th-largest army in the world, smaller than Yugoslavia's. This country was, by no means, a superpower.

The entire U.S. military possessed fewer than 500 heavy machine guns.

On Dec. 7, 1941, Johnny was encamped at New River when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Johnny's life changed in an instant. Anger, vengeance, vulnerability and a hardened sense of duty overwhelmed the Marines.

As if a surprise foreign attack on American soil wasn't bad enough, Johnny took another hit.

On Dec. 8, the Japanese bombed Manila.

Bunky Stowers remembers arguing with Johnny, who said Manila would never fall.

Manila John Basilone was wrong.

The Japanese stormed through the Pacific. Their army took Guam, Wake Island, the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor Island. The latter two battles were horrible, demoralizing defeats for the Americans and represented a virtual surrender of the Philippines, prompting Gen. MacArthur to say in retreat: "I shall return."

The Japanese's ultimate South Pacific prize - Australia - was on the horizon.

Sitting about 1,000 miles northeast of Australia was Guadalcanal, which was not a canal but a tiny Solomon island on which the Japanese had built a strip large enough to land bomber planes.

Realizing the grave significance of an enemy airfield so close to Australia, the Americans sent in the Marines. The First Division landed at Guadalcanal on Aug. 7, 1942, catching the Japanese by surprise. The Marines captured the air strip and renamed it Henderson Field after fighter pilot Lofton Henderson, who died in the battle of Midway.

The Japanese responded by sinking four cruiser ships (three American and one Australian) off the coast of nearby Savo Island, prompting a massive American retreat. Seventy-six ships, including those supplying and protecting the U.S. troops on Guadalcanal, left the area.

The Marines were alone. Japanese could strafe them any time they wanted. Nothing prevented their Imperial Navy from launching giant missiles from the sea.

Johnny arrived with the Seventh Marine Regiment at Guadalcanal on Sept. 17, 1942, about six weeks after the support ships had gone.

What he saw turned his stomach. The best fighting men the U.S. could muster, the vaunted First Marines, were diseased and delirious.

Soon, Johnny was one of them. He survived on roots and coconuts. When he was lucky, he would find old supplies left by the Japanese. He tossed away the worms and ate the rice.

Johnny's eyes seemed to sink into his skull. He lost 25 pounds. Sores on his feet became infected. At times, Johnny went barefoot to ease the pain. Mosquito bites turned into malaria. He was issued four quinine tablets a week to fend off the fever. He lived in a pup tent near a four-foot-deep fox hole, sharing the muddy ground with rats and lizards.

Guadalcanal was a sloshy, rotting jungle. Johnny could smell the decaying flesh. Japanese planes dropped bombs on the Marines three or four times a day.

"It was one stinking hell hole," said Richard Greer, one of Johnny's Marine buddies. "We stayed wet the whole time."

But Johnny kept his wits. As a sergeant, Johnny was in charge of 14 men and four .30-caliber, water-cooled Browning machine guns. One day, Greer said, Johnny secretly left his company and headed to Henderson Field, where he made an unauthorized inspection of several abandoned planes.

He searched them for machine guns, pulling out the best he could find.

Commanded by Col. Lewis "Chesty" Puller, who got his nickname because of his puffed-up, chest-first gait, the 7th Marines strung thousands of yards of barbed wire around Henderson Field. Then, Puller positioned a line of machine gun posts about 50 yards apart between the wire and the airstrip.

Johnny was on watch at about 10 p.m. on Oct. 24, 1942, when, over the roar of a tropical downpour, he heard the field phone ring.

Japanese troops were coming, straight at them. He later wrote that the first grenade hit by the time he hung up the phone.

He ordered his gunners to fire.

The guns on Johnny's left began their murderous assault. To his right, he heard an explosion.

Within seconds, Johnny got word that his right flank had been hit. He grabbed a machine gun and two men from the left flank and ran toward the right. The gun and tripod weighed 92 pounds.

The Browning was supposed to be stationary, not meant to be fired from the hip.

But as Johnny ran, he encountered eight Japanese soldiers. The Marines' line had been breached.

He cradled the gun in the crook of his left arm and, with the pink-hot rifle shaft blistering his skin, Johnny and his men killed them all.

When Johnny reached his right flank, all but two of his men were dead or incapacitated. One of their machine guns was demolished and the other was jammed.

Suddenly, the rain stopped.

For the first time that night, Johnny could hear the enemy.

As he frantically tried to repair the jammed gun, he could hear the thwack of barbed wire being cut.

Then he heard the screaming Japanese as they charged.

"MARINES,

YOU DIE."

REPORTING THE STORY

When

Army Ranger Pat Tillman died in April, Americans heard the story of the

ultimate sacrifice – a professional football player who walked away from

the limelight to serve his country. Just after Tillman’s death, reporter

Keith Sharon heard the story of Johnny Basilone, a WWII Marine who walked

away from a celebrity life to return to combat. Tillman will be honored

this week by the National Football League. Basilone will be honored this

week with a parade in Raritan, N.J., his hometown.This series was written

after dozens of interviews with people who knew Basilone, served with him

or had seen him speak on the bond tour. The research relied heavily on

the book “Raritan’s Hero” by Bruce Doorly and the book “Red Blood,

Black Sand” and video “The Saga of Manila John” by Charles Tatum.

Also, Basilone’s sister, Phyllis, wrote an extremely informative newspaper

series in the Somerset Messenger Gazette in 1962.Newspaper and magazine

articles were provided by the John Basilone Museum in Raritan, and Marine

Corps historic documents were provided by Faye Jonason.

FACTS

AND MEMORIES

Nov.

4, 1916 - Johnny Basilone born in Buffalo, N.Y.

(The

Basilones moved to Raritan, N.J., when Johnny was an infant).

Continued

in Part II ...Tomorrow